Home > News > Thomas offers a very attractive model of Christian intellectuality - Interview with Jan Aertsen

Thomas offers a very attractive model of Christian intellectuality - Interview with Jan Aertsen

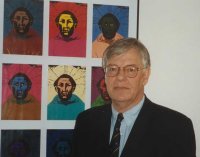

The Dutchman Jan Aertsen is professor of medieval philosophy and director of the famous Thomas Institut at the University of Cologne, Germany, since the beginning of 1994. But long before that, when he was still professor at the Free University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, Jan Aertsen was one of the 'founding fathers' of the Thomas Instituut at Utrecht.

What are you doing at this moment? Are you teaching any courses?Every semester I teach courses in which I also bring up some aspects of the thought of Thomas. For example, this summer I'll be lecturing on chapter 4 of Pseudo-Dionysius's On Divine Names. It is the chapter that deals with the Good, Light, Beauty, Love and Evil. In discussing this text I shall also take Thomass commentary into account.

Next, I am director of the Thomas Institut at the University of Cologne. For those readers who are less familiar with the work that is being done here, I want to point out that the name of our institute might be somewhat misleading. We do not focus exclusively on Thomas Aquinas, but on medieval philosophy - not so much theology - in general. The name of Thomas was chosen 50 years ago because he is an exemplar of medieval philosophical thought.

What research on Aquinas are you doing now?

Currently I am working on two long-term projects. The subject of the first one is transcendental philosophy in the Middle Ages from Philip the Chancellor (around 1225) to Suarez's Metaphysical Disputations (around 1600). The part that deals with Thomas Aquinas is already finished and has been published five years ago in Medieval philosophy and the transcendentals : the case of Thomas Aquinas.

The second project is about Meister Eckhart. For a long time the study of Eckhart was ruled by the so-called 'Aquinas-paradigm': Eckhart's texts were read and understood in concordance with the thought of Thomas. My predecessor at the Thomas Institut, Joseph Koch, represented this line of interpretation. Later, scholars like Kurt Flasch and Burkhard Mojsisch have argued that Eckhart is the principal medieval critic of Thomas. I want to show that the latter view is not correct although I do think that Eckhart goes his own way apart from Thomas.

What is the most important thing you learned from Aquinas?

The first important thing I learnt from Aquinas is conceptual clarity and care over the order of thought. In these things I consider him exemplary and I try to follow in his footsteps. Obscurity and fuzzy language are often mistaken as signs of deep thinking.

Next, I see Thomas as a very attractive model of Christian intellectuality, of the "two wings of the human mind" as the encyclical Fides et Ratio puts it. Gilson's notion of 'Christian philosophy' has been heavily criticised but many scholars actually work - and live - in accordance with it. Although I think that Gilson went too far, especially in his L'esprit de la philosophie médiévale, by laying down the 'metaphysics of Exodus', the metaphysics of esse, as the standard for Christian philosophy. In doing so Gilson got himself into trouble because it led to the exclusion of e.g. Eckhart and Pseudo-Dionysius from Christian thinking. And why would a metaphysics that is more essentialist or takes its point of departure in goodness instead of being, be less Christian?

What works of Aquinas are you most familiar with?

I don't want to sound too immodest but I read most of Aquinas's works and with many of them I am rather familiar. Somewhat less with his exegetical works except for the commentary on John. It would be a very interesting project to trace the medieval tradition of commenting on John. Maybe one day I shall have the time to do that.

What is the importance of Aquinas-research for our times?

I can answer that question only from the perspective of philosophy. First, when I teach I try to present the importance of Aquinas for the reflection on the classical questions of metaphysics, like the questions of goodness and being. I think that Aquinas raises these questions in an exemplary way that can stimulate our students.

Secondly, I consider Aquinas as an inspiration for Christian philosophy, that is, for doing philosophy in a Christian context. One benefits from working with his approach. It is especially his openness to other traditions that I appreciate. He is not a fundamentalist but he is curious and adopts whatever truth he finds in Aristotelianism and Neo-Platonism without fear of getting lost or becoming tainted with unchristian elements. He integrates it in his own thinking in an open way although he knows very well that they are pagan traditions. Aquinas is rightly convinced that revelation or faith and natural reason or philosophy cannot contradict each other and he warns for defending the faith with wrong arguments.

What are your expectations of the Thomas Instituut?

I was involved in establishing the Thomas Instituut at Utrecht. The institute gave and gives a new and important impulse to Aquinas-research in the Netherlands, especially as far as theology is concerned. For philosophy it is somewhat different. I think that there should be more interest in philosophy, e.g. in the Yearbook of the institute.

What do you think of the Internet in general and in what manner could the Thomas Instituut make better use of this medium?

It is hard for me to say anything useful about the Internet because I have never worked with it. But I have planned to catch up with it this summer. Some time ago I had an experience that really opened my eyes. In an introductory course I asked the students where they would look to find some basic information on Philip the Chancellor. I expected (or hoped) them to mention the usual encyclopaedias and repertories but one of the students answered: 'The Internet'. My expectations didn't run high but to my surprise the student came back the next week with a whole stack of articles and papers about Philip that he had downloaded from the Web.

Which of your books/articles do you consider the most important?

The most important are my Medieval philosophy and the transcendentals: the case of Thomas Aquinas (Leiden etc.: Brill, 1996) and my dissertation Nature and creature: Thomas Aquinas's way of thought (Leiden etc.: Brill, 1988).